I was recently asked to write an essay for Writer’s Digest about the challenges of turning real people into characters in memoir. This is something I’ve thought a lot about (and agonized over, and struggled with)—it’s even the subject of an essay in First Love, a kind of meta examination of a central challenge of the project as a whole. Negative Space was in many ways one long character sketch of my father. But despite having thought a lot about the particularities of character work in my own writing, when I sat down to write that essay for Writer’s Digest, what came out was… a bunch of thoughts about Edwardian-era painter John Singer Sargent.

I eventually cut all of that material to write a more straightforward craft essay, and, well—here it is, reconstituted into the second installment of Museum Pages. (If you missed the first installment, about Edward Hopper and the messy early stages of essay drafting, you can read it here.)

But first! Tomorrow is the last day to get 20% off the cost of my upcoming seminar, The Braided Essay! Register today and come write a brand new essay from scratch—whether you have a topic in mind or not.

Sargent was the first painter I ever declared “my favorite,” at nine years old, which positively delighted my artist father. An avid collector of second-hand, thrifted, and “borrowed” art books himself, he bought me a brand-new, glorious, hardcover book of Sargent’s paintings for my tenth birthday. I pored over the book for hours whenever I was at his apartment (where we kept the book), each time marking a new favorite painting with a Post-it.

When the Morgan Library put on an exhibit of Sargent’s portraits in charcoal a few years ago, I was in the early stages of writing the first few pieces in my essay collection, still wrapping my mind around the ways that an essay collection is both more fun and, in some ways, more work than a memoir. Deep in the throes of drafting, I mostly wasn’t leaving the house unless I had to, but for Sargent I would make an exception. It felt like an old friend was coming to town; like it would be unacceptably rude for me to be too busy to see him.

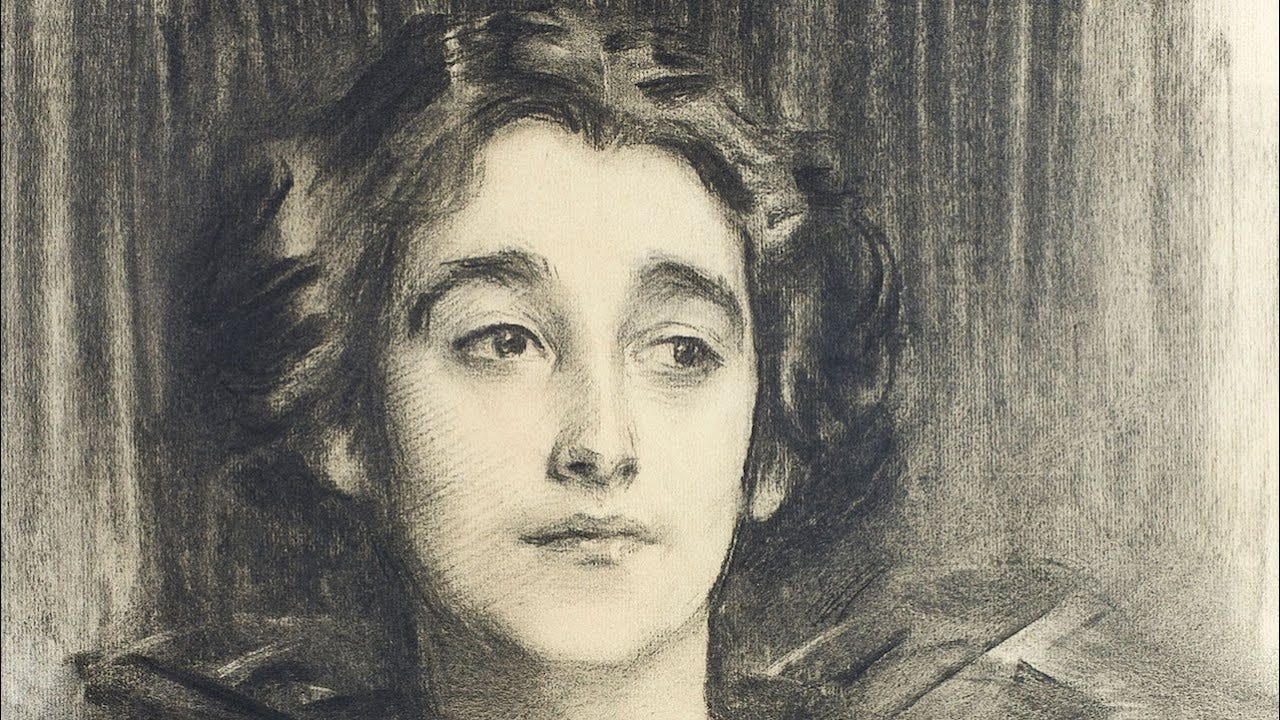

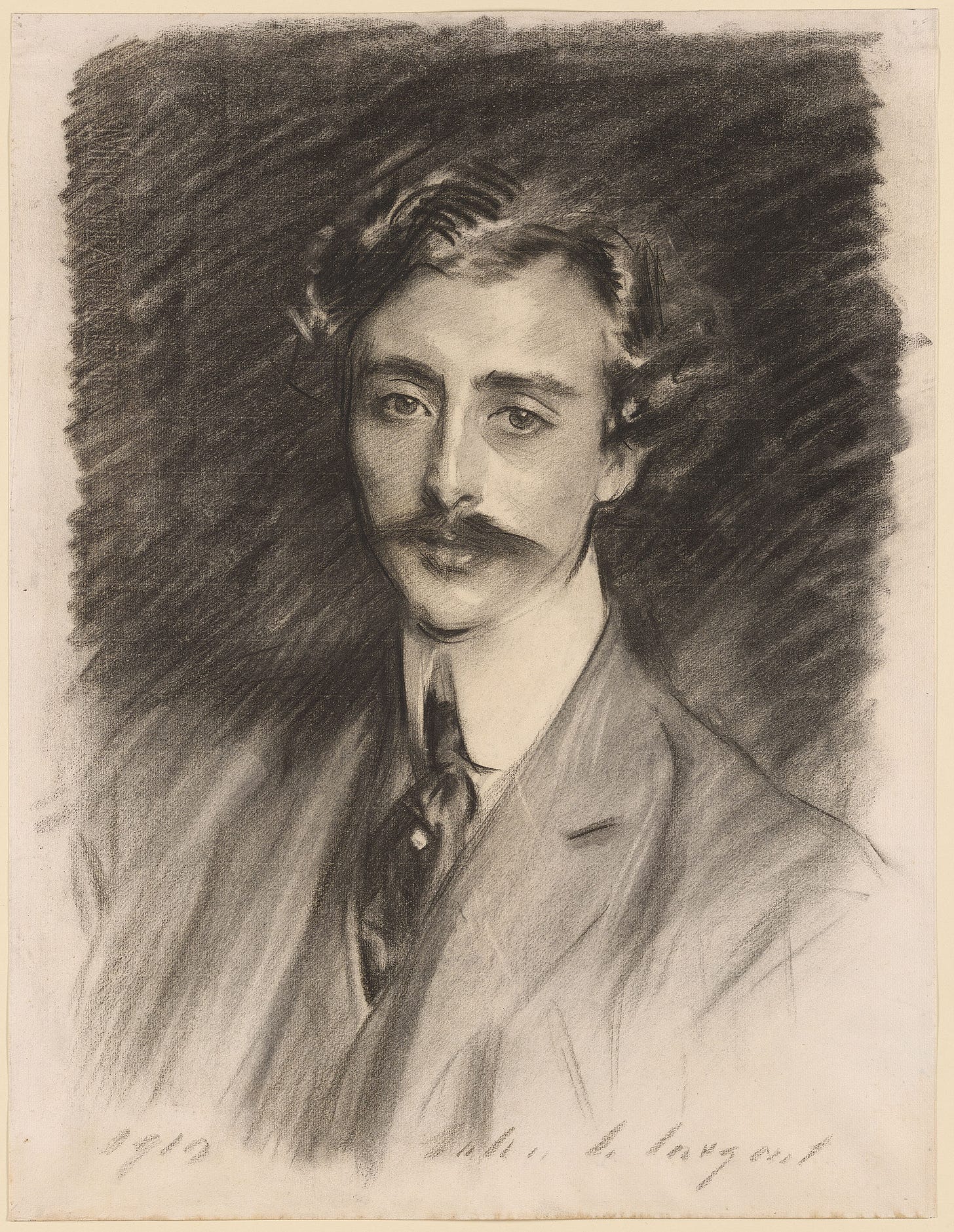

I was sharply aware of each and every hour spent away from my desk, each break from writing feeling like an indulgence. But as soon as I stepped into the gallery and saw dozens of early 1900s ladies and gentlemen in their gowns and topcoats smiling, smirking, and scowling at me as if they were ready to step right out of their frames, it was clear what I was looking for here, consciously or not: a clue as to how to achieve the impossible alchemy of representing real people. This was, of course, not a break from the work, but part of it.

Capturing all the many facets of my father in Negative Space—the exact balance of dourness and humor, woundedness and severity, tragedy and brilliance; the way of interacting with the world that was embodied so perfectly by the contrast between the exaggerated slouch of his protectively rounded shoulders and his bright, searching, upturned eyes—was hard enough with 275 pages to work with. But now in 15 different essays, I wasn’t just trying to capture one complicated character, but a whole ragtag cast. In some essays I had only a few pages, sometimes just a paragraph or two, in which to bring a friend to life.

I made voluminous lists of characteristics and quirks, details and habits and adjectives to describe each friend’s physicality, voice, tendencies, tenor; how I felt around them and what they meant to me. It all felt like far too much to manage, especially in the essays that were not exactly about the friend, but about a shared experience, so the friend needed to be visible on the page but without stalling the narrative momentum. How to reproduce backstory and inside jokes and idiosyncrasies, but in passing, without the reader realizing that I was taking up time describing someone?

I’d already begun to think of character work as portraiture (“Portraiture,” in fact, is the title of the essay on this topic in First Love), and once I was in the gallery at the Morgan, I wondered why it hadn’t occurred to me sooner to turn to my favorite portraitist for guidance.

The goal of portraiture—whether painted, photographed, or written—is deeper than a “realistic” representation; the goal is to capture the essence of a person. Who they are, not just the external facts of what they look like. Sargent’s portraits achieve this to an uncanny degree: Sure, they’re realistic, but they also achieve something much greater than realism—they look alive. They have personality. (On a recent visit to the Met, walking through the American Wing, my husband Soomin commented that Sargent’s portraits are so good because “you believe him.” And it’s true—his portrayals feel too perceptive and precise to be anything but faithful.)

At the portraiture exhibit, I felt that I was getting a glimpse of each subject’s truest self; something much more meaningful and much more ephemeral than the shape of their jaw or the style of their dress. And, importantly, I didn’t need to see everything about them to feel this way.

These drawings don’t depict everything about a person, their whole lives and all their iterations of self (all of the backstory and inside jokes and idiosyncrasies I was overwhelmed trying to fit into my essays). They each capture a person as they appear in a single, fleeting moment in which they are truly themselves. And they do this not through the volume of detail, but in the right details: This socialite’s tense, pursed lips; that art collector’s sleepy bedroom eyes; this banker’s flared nostrils.

That is: you don’t need to include everything about a person for a portrait to be successful. I knew this, of course. But seeing the charcoal portraits—some of which dissolved into vague gestural lines below the shoulders; the squiggle of a suggested shadow behind the hair—solidified it for me in a way that no amount of reading great character descriptions had. A single still image is, by necessity, limited in scope. This constraint helped me see just how much a few perfect details can do—whether in a drawing or a short essay. That it wasn’t about how to include everything, but about choosing carefully what to include.

Walking through the gallery, I could feel the descriptions I was writing of my friends shedding layer upon layer of crowding, unnecessary information, crystalizing into brief snapshots that said everything they needed to say: The sound of Heather’s guffawing laugh; Leah’s long curly hair always trailing behind her in constant motion; Sabina’s preference for champagne, even in dive bars.

PS My essay on characters in memoir will be in the March/April print issue of Writer’s Digest—I’m hoping it’ll be available online too, and I’ll send out a link if it is.

Smart post about how to be better at looking. Sargent gives us so much to consider and weigh. ❤️

So excited to find another daughter of NYC painter writing, thrilling. My mother loved Sargent. My father was an admired portrait painter. Now to track down your memoir.